Creating Safety After Chaos: How to Build an Emotionally Regulated Life Post-Trauma

By Dr. Kate Truitt

Have you ever watched someone freeze in a moment that should feel safe? That’s the nervous system, still living in yesterday’s chaos. Even when the danger has passed, the body can remain on high alert, bracing for what might come next. For many survivors of trauma, especially domestic violence, safety isn’t just about where you are, it’s about how your brain and body are still carrying where you’ve been.

So what happens when the world finally gets quiet, but the brain doesn’t?

This is one of the most tender and complex parts of healing. After experiencing prolonged stress or harm, the brain learns to expect the worst. Stillness can feel like vulnerability. Calm can feel unfamiliar, even unsafe. The very moments that should offer rest and peace can stir up anxiety, fear, and emotional overwhelm. This isn’t a failure, it’s biology. It’s the survival brain doing exactly what it was wired to do, long after it’s needed.

As clinicians and healers, we hold space for this dissonance every day. We witness the courageous work it takes for someone to lean into healing when their nervous system is still echoing the past. We know that healing isn’t just about removing harm, it’s about building safety, structure, and self-trust from the inside out.

How Trauma Resets the Brain’s Compass

One of the most important things we can offer the survivors we support is this: validation that their responses make sense. Trauma changes the brain. It doesn’t just create painful memories. It reshapes how the brain processes threat, safety, and emotion.

When someone experiences domestic violence or chronic stress, the brain’s alarm system, specifically Amy, the amygdala, becomes hyperactive. This part of the brain is designed to detect danger and keep us alive, but it doesn’t differentiate between a memory and a moment. If a smell, sound, or glance feels similar to a past threat, the amygdala can sound the alarm all over again, sending the body into fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

At the same time, the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for logic, decision-making, and emotional regulation, often goes offline during trauma. This is why survivors may later say things like, “I don’t know why I stayed,” or “I couldn’t think clearly.” Their brain was protecting them in the only way it knew how, by prioritizing survival over strategy. In this psychoeducational video , I delve deep into why our brain remember traumatic experiences for a very long time.

Over time, this pattern creates a nervous system that becomes stuck in high alert. The world feels unpredictable, even when it isn’t. Relationships feel risky, even when they are safe. Emotions become intense and difficult to manage, not because someone is weak or broken, but because their internal compass has been shaped by the need to survive.

Understanding this neurobiological shift gives us a framework to help survivors rebuild a sense of internal safety. It also reminds us that healing is not about getting over it. It is about helping the brain learn that it is safe enough to slow down, connect, and feel again. We stop asking “What’s wrong with you?” and start asking, “What happened to you?”

And that’s where healing begins.

What Does Emotional Regulation Actually Look Like?

We often talk about emotional regulation as a goal of healing, but what does it mean, and what does it look like in everyday life?

Contrary to popular belief, regulation is not always about being calm. It is not about avoiding big emotions or having perfect control over every reaction. Regulation is about having the ability to notice what we are feeling, stay connected to ourselves in the experience, and make choices about how to respond. For trauma survivors, especially those who have lived in unpredictable or unsafe environments, this process can feel foreign or even impossible.

At its core, emotional regulation involves three key skills.

- Awareness. This means recognizing what is happening inside including physical sensations, emotional states, and thought patterns. For many survivors, this step alone can be overwhelming.

- Tolerance. The capacity to stay with those emotions without immediately reacting, shutting down, or numbing out.

- Modulation. The ability to shift or soften the emotional experience in a way that feels safe and empowering.

These are not skills we are born with. They are learned, and often, in the case of trauma, they need to be relearned. Emotional regulation begins with creating consistent moments of safety. Sometimes that is as simple as learning to pause and take a breath. Sometimes it means building rituals into the day that give the nervous system cues of predictability and control.

As clinicians, we can model these skills in the therapeutic relationship. When we show up regulated and grounded, we become a safe nervous system for our clients to mirror. Over time, this co-regulation helps lay the foundation for self-regulation, giving survivors a felt sense of what it means to stay with themselves, even in discomfort.

Creating Internal Safety

Safety is not just a place, it is a feeling. For trauma survivors, especially those who have lived through domestic violence or other forms of chronic threat, the concept of safety can feel complicated. The internal world may feel turbulent even when the external environment becomes calm. In this short video , I share a few tips on cultivating a sense of safety in dangerous environments.

One of the first and most important goals in trauma recovery is helping clients create a sense of internal safety. This is the foundation for emotional regulation, self-trust, and healing. But it is not something that just happens. It must be cultivated intentionally and consistently.

So, what does safety feel like in the body? It is often subtle. A slow breath that reaches the belly. Shoulders that soften. The ability to be still without panic rising. A moment of quiet where the mind does not race. These signs may seem small, but to a trauma survivor, they can be revolutionary.

Neuroscience reminds us that the brain is shaped by experience. This means that just as the brain was shaped by fear, it can also be reshaped by safety. The process of rewiring the brain is called neuroplasticity. Every time we help clients notice a safe moment, hold a regulated state, or connect with a sense of peace, we are helping them build new neural pathways. These moments may be brief at first, but with repetition and intention, they grow stronger.

There are many ways to begin creating safety. Some clients benefit from grounding techniques, like feeling their feet on the floor or holding onto a comforting object. Others respond well to breathwork, movement, or sensory routines that bring predictability to their day. Therapeutic touch, such as in Mindful Touch or EMDR, can also help the body release stored stress and access calm.

It is important to remember that the path to safety is not linear. There will be days when the nervous system reactivates and fear returns. This is not failure. It is simply the brain doing what it has learned to do. Our role is to meet those moments with compassion and curiosity, helping clients understand what is happening inside and guiding them back to safety, one experience at a time.

Structure as a Healing Strategy

When someone has lived through chaos, structure can feel like oxygen. For survivors of trauma, especially domestic violence, life may have felt unpredictable for a very long time. The body remembers that unpredictability, and the nervous system stays alert, always scanning for the next danger. Even after the immediate threat is gone, that internal state of alertness can remain.

This is where structure becomes not just helpful, but healing.

The trauma-impacted brain craves consistency. It is soothed by patterns. It relaxes when it knows what to expect. That is why even small, predictable routines can create powerful shifts in the nervous system. They send signals to the brain that say, you are safe now. You can rest.

Structure does not have to be rigid or overwhelming. In fact, healing often begins with the simplest steps. Waking up and going to bed at the same time each day. Eating meals at regular intervals. Setting a soft alarm to pause and breathe every few hours. Keeping a gentle rhythm to the day helps the body find its own internal rhythm again.

Creating these micro-structures also offers survivors something incredibly important, a sense of agency. Trauma often strips away a person’s sense of control. Establishing structure, even in small ways, gives that control back. It allows someone to say, this is mine. I get to choose this moment.

Clinically, we can support this process by helping clients identify where they feel most dysregulated and building in anchor points throughout the day. These might include a grounding breath before leaving the house, journaling after therapy sessions, or using sensory cues like calming music, a favorite scent, or even warm tea to help the body settle.

Structure gives the brain and body a predictable framework. Within that framework, safety can begin to grow. And from that safety, resilience has room to emerge.

Rewriting the Rules of Self-Worth After Domestic Violence

One of the most painful impacts of domestic violence is what it teaches a survivor to believe about themselves. Over time, the brain begins to internalize the messages of abuse. I am not safe. I am not worthy. I do not matter. These beliefs are not born from truth, they are born from survival.

Silence, shame, and guilt are three of the most common emotional responses in survivors of DV. At first, they serve a protective purpose. Silence keeps the peace. Shame keeps attention off the self. Guilt gives a sense of control. If I caused this, maybe I can fix it. But while these emotions may help someone survive an unsafe environment, they can become deeply damaging when the danger is gone and healing begins.

What is important for clinicians to know is that these beliefs are not logical, and they are not always conscious. They live in the parts of the brain responsible for emotion and memory, especially in the amygdala and hippocampus. This is why survivors often struggle to articulate what they feel or why they react the way they do. The trauma lives in the body, not just the story.

Helping someone rewrite their beliefs about self-worth requires deep patience, safety, and trust. It also requires us, as practitioners, to gently reflect a different narrative. You are not to blame. You were surviving. You are worthy of care. You have value simply because you exist.

To support this journey of healing and self-awareness, I’ve created the SHAPED Framework Self-Discovery Worksheet to guide individuals in exploring how their past experiences and learned behaviors are influencing their present lives—and how to move forward with clarity, resilience, and empowerment.

There are powerful tools we can use in this process. Neuroscience-informed approaches like Mindful Touch, EMDR, and parts work help access the emotional brain in ways that words alone cannot. Compassionate inquiry, self-reflection exercises, and narrative therapy can also support survivors in identifying the core beliefs that no longer serve them and replacing those with truths rooted in strength and resilience.

As we begin to help survivors rewrite their story, it is vital to honor the brilliance of their survival. The very patterns that feel stuck or frustrating now once kept them safe. When we meet those parts with respect and curiosity, we make space for healing without shame.

Healing Through Connection

Healing from trauma does not happen in isolation. While trauma often occurs in relationship, healing must also happen in relationship. This is especially true for survivors of domestic violence, where the very space that should have felt safe became the source of harm.

After trauma, connection can feel like a risk. The nervous system may interpret closeness as a threat, even when the person in front of us is kind and supportive. This is not a sign of dysfunction. It is a sign of protection. The brain is doing what it learned to do, keeping someone safe by avoiding what once caused pain.

This is where co-regulation becomes one of the most powerful tools we have in the healing process. When we show up calm, grounded, and attuned, our nervous system becomes a model of safety for the survivor’s brain to mirror. Over time, and through repeated experiences, the brain begins to learn, this is what safe connection feels like. I can be with another person and still stay with myself.

For clinicians, this means that our presence matters as much as our techniques. Our tone of voice, our facial expressions, our ability to stay regulated in the face of emotion, all of these become the environment for healing. We are not just offering tools, we are offering ourselves as a safe space for the survivor’s nervous system to gently recalibrate.

Of course, this also means we must be mindful of our own regulation. Trauma work can be activating. Holding space for pain, fear, and grief requires that we stay grounded in our own bodies. When we take care of ourselves, we create a more stable, trustworthy container for our clients.

Connection also means helping survivors build supportive relationships outside the therapy room. This might look like slowly re-engaging with community, setting boundaries with family, or learning to trust a friend. It may be as simple as making eye contact at the grocery store or feeling safe enough to sit in a crowded café. These micro-moments of connection matter. They tell the brain, you are not alone, and it is safe to be seen.

The Phoenix Process

Healing after trauma is not about going back to who we were. It is about becoming someone new, someone who has walked through the fire and lived to tell the story. This is what I often call the phoenix process. It is the quiet, powerful rise that happens when someone begins to reclaim their life after devastation.

For survivors of domestic violence, this journey is rarely linear. It is layered, emotional, and often filled with moments of doubt. There may be times when progress feels invisible and days when survival feels like the only goal. That is not failure. That is healing in motion.

The phoenix does not rise all at once. It rises in small decisions. Choosing to pause and breathe instead of panic. Choosing to say no for the first time. Choosing to trust, even just a little. Choosing to believe that healing is possible, even when it still feels far away.

As clinicians, we walk alongside this journey. We witness the courage it takes to confront what was and reach for what could be. We help survivors move from survival patterns to empowered choices, from self-blame to self-trust, from fear to hope.

This process also involves rewriting the story of identity. Trauma often defines who someone thinks they are. I am broken. I am weak. I am to blame. The phoenix process is about shifting that narrative. I am strong. I am wise. I am still here.

Neuroscience reminds us that the brain is always changing. This is the beauty of post-traumatic growth. With support, intention, and compassion, the brain begins to integrate the trauma and build new pathways rooted in resilience, meaning, and purpose. The scars do not disappear, but they become part of a larger story, one where the survivor becomes the author again.

And now, we have tools that can literally put that healing power back into your own hands. My book, Healing in Your Hands is the first book of its kind to integrate the neuroscience of trauma with self-healing tools.

Event Spotlight: Silence, Shame, and Guilt in Domestic Violence Recovery

The journey of healing after trauma is layered, and for survivors of domestic violence, it is often shaped by three powerful and deeply misunderstood emotional states: silence, shame, and guilt. These responses are not signs of weakness, they are survival tools. But over time, they can quietly erode a person’s sense of self, safety, and worth.

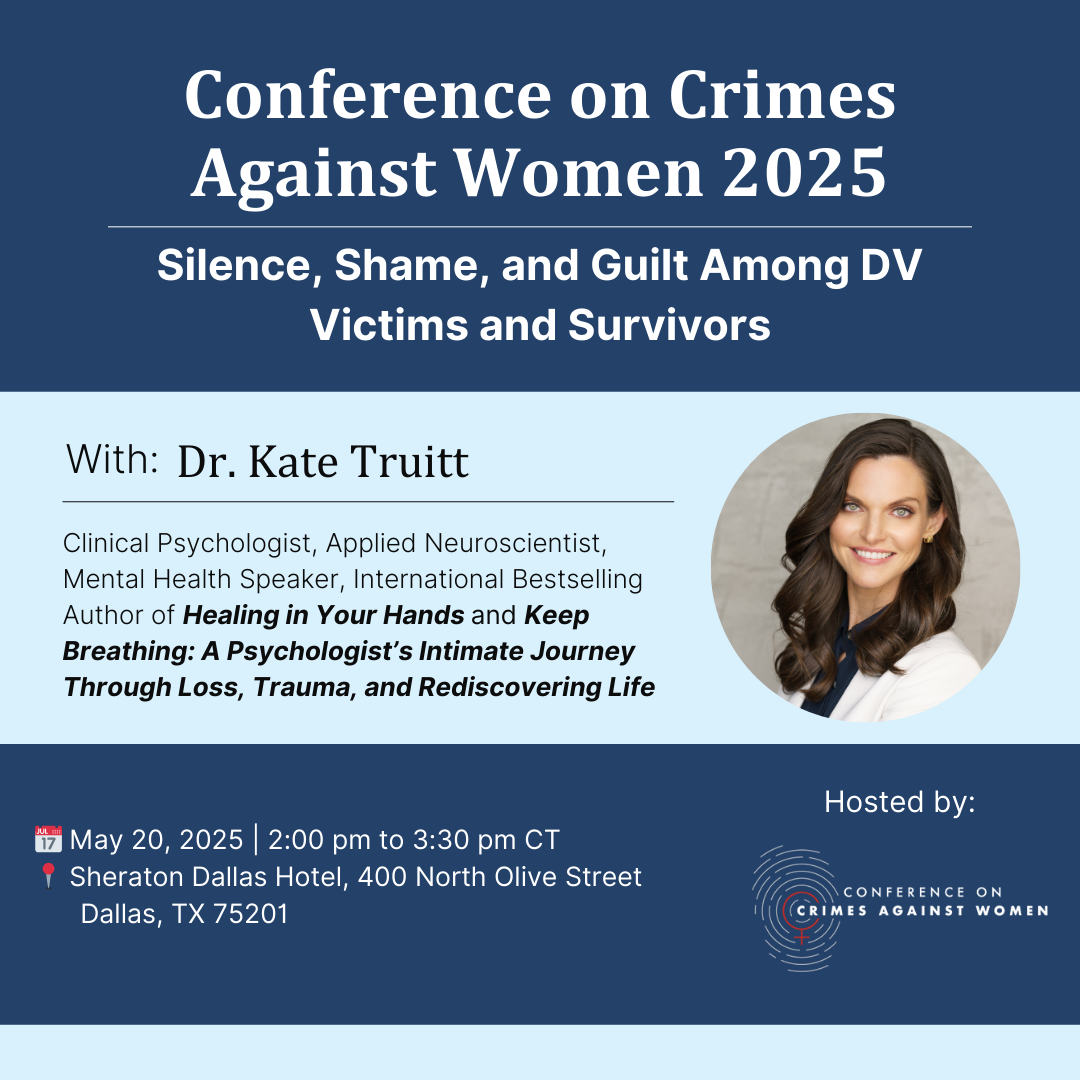

I invite you to join me for an upcoming workshop hosted by Conference on Crimes Against Women where we will explore these themes through a neuroscience-informed and compassion-driven lens.

During my 90-minute workshop, we will explore the neurobiological roots of shame and guilt, especially in the context of domestic violence. We will examine how these emotions are encoded in the brain and how they impact a survivor’s sense of identity, emotional regulation, and decision-making long after the danger has passed.

Most importantly, we will talk about how to break these patterns. Using science-backed strategies and trauma-informed interventions, I will share tools for helping survivors build self-compassion, reconnect with their inner strength, and reclaim their voice. You will leave with actionable techniques to bring back to your clinical work, as well as a renewed sense of hope for what healing can truly look like.

Whether you work with survivors in individual therapy, group settings, advocacy, or community care, this workshop is designed to support and empower your practice.

Together, we can help rewrite the story of what it means to heal. Register through this link.

Breathing Into Safety

Healing after trauma is not about fixing what is broken. It is about coming home to the parts of ourselves that were forced to hide, adapt, or go silent in order to survive. Creating safety after chaos means helping those parts feel seen again. Heard again. Whole again.

For survivors, especially those navigating the aftermath of domestic violence, healing begins with one powerful truth. You are not what happened to you. You are who you choose to become in the moments after.

To the clinicians, practitioners, and advocates doing this sacred work, thank you. You are the lighthouse that helps others find their way. Not by doing the healing for them, but by holding steady while they remember how to rise.

Safety is not a destination. It is a practice. A breath. A pause. A return to self.

I hope you will join me on May 20 in Dallas for Silence, Shame, and Guilt Amongst DV Victims and Survivors. Together, we will deepen our understanding of the trauma brain and expand our capacity to hold space for healing, for growth, and for hope.

Because healing is possible. And together, we can help make it safe to begin.

References

- Mental Health Writer. (2024, December 19). From chaos to calm: Strategies for managing PTSD after natural disasters, crimes, and accidents. Resources to Recover. https://www.rtor.org/2024/12/19/from-chaos-to-calm-strategies-for-managing-ptsd-after-natural-disasters-crimes-and-accidents/

- Arbeláez, L., Peña, A., & Orozco, J. (2021). La neurociencia y su relación con la psicología clínica. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 21(2), 1–19. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/279/27962050025/html/

- D.A.V. (Domestic Abuse Victim) Charities. (n.d.). How to help children overcome the trauma of domestic violence. D.A.V. Charities of Riverside. https://dvapriverside.org/how-to-help-children-overcome-the-trauma-of-domestic-violence/

- Warshaw, C., Sullivan, C. M., & Rivera, E. A. (2013). A systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212470543